THE CLEARING

/I’ve been circling this bit for several days, divided by a desire to put down some thoughts about The Clearing, a moving and quite profound installation piece at the Agnes (but only until November 9, so dig out your runners and get going!), and also a feeling that I’m not going to do it justice, my head these days so full of real estate lingo, that dim three-bed, two-bath approach to aesthetics.

The Clearing, featuring work by Marney McDiarmid and Clelia Scala, with vital contributions from sound artist Matt Rogalsky, poet Sadiqa de Meijer, and painter Lee Stewart, is set mostly within a painted shipping container disguised as a glitchy stretch of waterfront, which promises at its entrance “to transport viewers from a space of global commodity to an organic ecosystem that values introspection, delight, and connection”.

I would argue that it accomplishes much more than that.

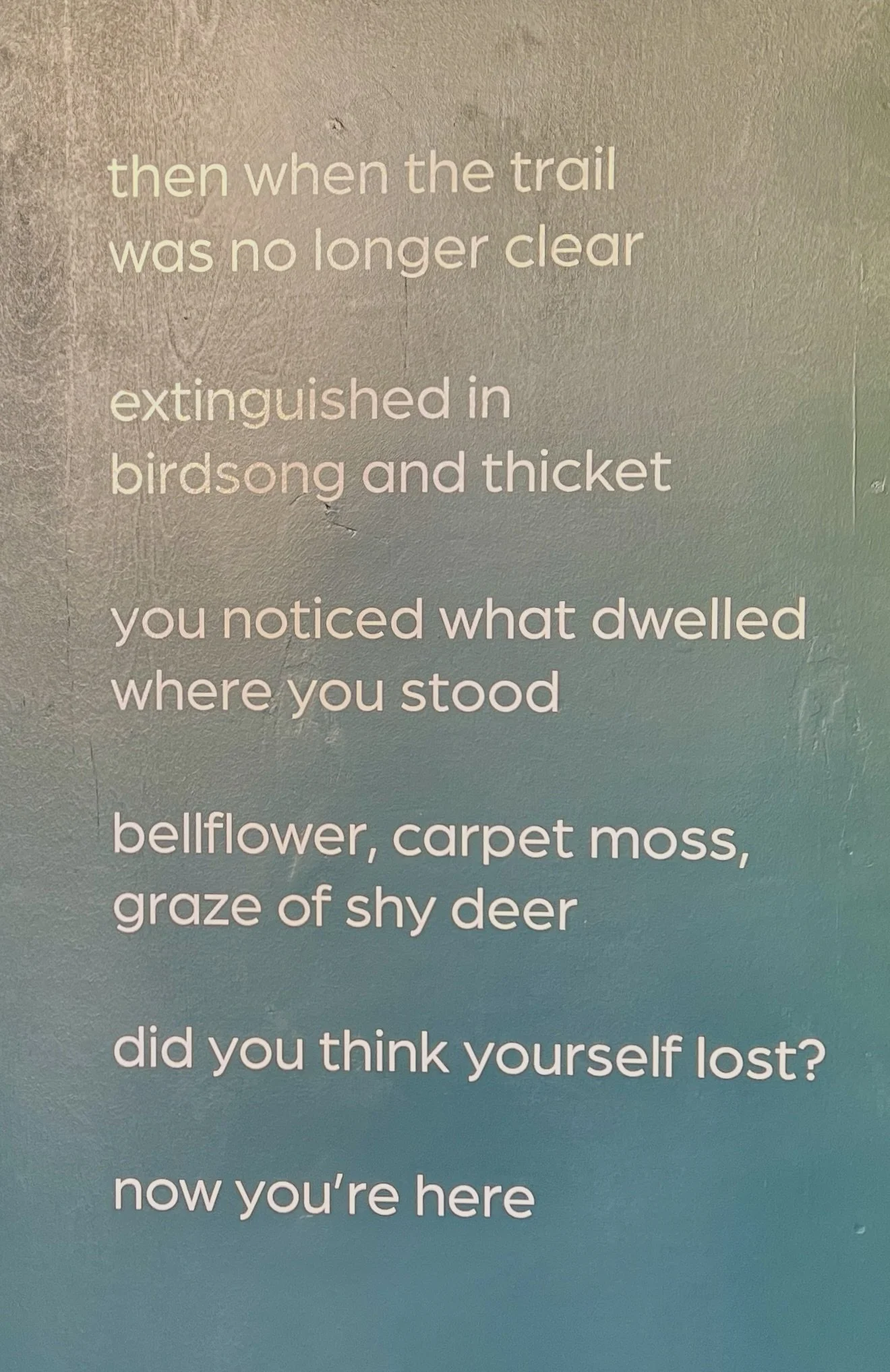

An invitation from Sadiqa de Meijer just inside the steel door (it ends “did you think yourself lost / now you’re here”) is more intriguing. Her words tether the work to the earth, like a balloon to its basket, but at the same instant set it free. They are fine as a silk net, a thirty-five-word murmuration.

McDiarmid works primarily here with clay fired into glossy rounds of lichen, partly unwound scrolls of tree bark, mysterious and sensual blooms of orchid, sprouting leaf and aching tendril. I remember a long-ago mushroom trip that provided similar visuals.

Scala’s creations are just as dreamy, only darker. There are more absurdly convincing lengths of tree bark and moss, but also flocks of birds wrought from sculpted and written-on paper that feel like extrusions of scorched meringue. Her birds sport menacing expressions reminiscent of Kabuki theatre, and some are only just beginning to burst through the container’s metal skin, as if appearing suddenly, shockingly, in stormy sky.

The idea is that you carry a flashlight with you, and in humid darkness you illuminate the artists’ work(s), which are either mounted on the container’s walls, or strung from its ceiling on glassy monofilament. Exploring this way, giving it a really forensic once-over, throws shadows onto the corrugated walls, making dimmer, monotonal versions of everything (Plato’s Cave anyone?). The work swarms over and around you, as if you’ve fallen into a hive.

It is a moving work, both lovely and a little frightening, with a soundtrack as rough-smooth as felt. Its extremes seem fitting to the age. The constant, toxic flood of goods over our oceans and through our skies, along our roads, impact the natural world’s life expectancy, and the tension between what we are born into, and what denuded scraps we may leave behind, is contained in every mute squawk, every stripped tree, every glistening fungal patch.

Visitors are invited upon entering to shred papers they have brought with them, to destroy any language that leaves them unsatisfied or empty, and to add that litter to the forest floor, where it will either soften footfalls, I suppose, or fill up the space until it is unbreathable. I think if I could fold time upon itself I’d have brought the first few drafts of these paragraphs with me when I visited. And maybe tomorrow, knowing I still haven’t come close to capturing the magic I saw, or any of the intensity I felt, I’ll return with these.